(Part 1)

If we’re going to achieve the relatively dramatic speculative goals laid out in part 1 of this series, it’s going to be essential to find financial instruments which are incorrectly priced and for which we can thus predict future price movement. But before we can do that, we need a solid understanding of the source of those pricing mistakes and how to detect them.

Thankfully, this is not a place where we have to re-invent the wheel. The last few decades have produced some excellent academic work on mis-pricing, and in my opinion by far the best comes from Robert Shiller. We’re probably lucky the man’s an academic rather than a trader. His academic work, broadly speaking, is focused on refuting the efficient market hypothesis with data – that is, finding situations in which the market moves in predictable ways. In Off-Road Finance terminology, his career has been a hunt for naive markets. And he’s had no trouble finding them – he didn’t even have to go look in weird places. I’ve already written about how he demonstrated that housing prices move in big, slow, smooth curves. That’s only one of the biggest markets in the world, and it’s about as efficient as my old Ford Explorer (15mpg baby!). Unfortunately for our speculative purposes, it’s somewhat difficult to trade housing in a stock like instrument. Otherwise that data would be of great use to us. But never fear – Robert Shiller has also turned his interest to the stock market, and his findings there are only slightly less striking.

In order to understand stock valuation, Shiller started with a concept most people should be familiar with: the price to earnings (or PE) ratio. The PE ratio is the most basic of fundamental analysis tools. It works on the assumption that the reason people own shares in companies is because those companies earn money. The ratio then describes what you’re paying for those earnings. A PE of 15 means that a share of stock costs $15 for every $1 of yearly earnings. An easy way to think about PE ratios is that the represent the time (in years) the company would take to pay back your investment assuming they paid 100% of earnings as dividends and operations didn’t change (grow/shrink) over that time. Of course, the company in question probably doesn’t pay 100% dividends – they most likely retain some or even all of their earnings. We’ll come back to those retained earnings in a bit.

The PE ratio suggests a simple trading method: take a population of stocks and buy the lowest PE stocks. If a dollar earned by GE really is as valuable as a dollar earned by Apple (and it’s hard to argue otherwise) then you should be well served by such a policy. Historically this trading strategy was known as “dogs of the DOW” when the population of stocks was DOW stocks. Later it was revamped as the “Foolish Four” and became a best selling book. Unfortunately the dogs/foolish strategy pretty much stopped working right after the book came out. It’s hard to say to what extent this was due to the book creating a hostile market vs. general stock market malaise in the last 15 years. It’s also possible that the managment at troubled DOW firms got worse. In any case, PE ratio by itself probably isn’t going to make you rich.

The most obvious reason the PE ratio isn’t a key to riches is that the earnings of companies aren’t constant. They grow and shrink as a company’s business improves. Frequently a high PE merely reflects a rational belief that the company will grow (this is commonly referred to as a growth stock) whereas a low PE reflects the belief that the company will shrink. Similarly, companies have substantial ability, via accounting tricks, to move earnings forward or backward in time. This sort of manipulation plays havoc with the PE ratio.

OK, so the PE ratio has problems. But we still want to understand the valuation of stocks. Enter Robert Shiller with the best possible solution to the problem: big data. Shiller made two simple changes: instead of calculating PE for one stock, he used every single stock in the S&P 500. And instead of using current earnings, he used average earnings over the past 10 years. So instead of needing 2 pieces of data (current price and previous quarter’s earnings) the calculation now took 5,500 – 10 years of earning plus current price for 500 stocks. Obviously big data doesn’t make your life any easier computation-wise, but it goes a long ways towards cleaning up messy data. Averaging the earnings over time renders accounting tricks meaningless. Averaging across companies renders the growth stock issue meaningless – one company may have better growth prospects than another, but the prospects for the market as a whole are fairly constant.

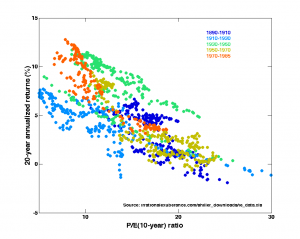

With this new data in hand, we can ask a basic question: how does the price of stocks (expressed as Shiller PE) affect their performance. Thankfully, some nice person on Wikipedia has worked up a handy chart:

I suggest you spend a little time with this chart – it’s surprisingly deep and informative. Some takeaways:

- Market returns are inversely correlated to Shiller-PE price and the effect is very dramatic.

- It’s basically impossible to generate market returns in excess of about 10% on average. Typical results are more like 5%. Anyone claiming that 10% is easy to achieve with a broad market approach is fooling you (and likely trying to get their hands on your money).

- The market under-performs its pricing more often than not. For example, if you look at the points at PE=10, most of them return less than 10% per year. Similarly, most of the points around PE = 20 return less than 5% per year. This long-term under performance of the broad market is an interesting topic, and is probably related to poor use of retained earnings by firms.

- It takes a long time for returns to be realized – the time scale is 20 years for a reason. Otherwise many more of the datapoints from the late 1920s would be negative.

- This effect has been remarkably constant over ~100 years of history

- Shorting stocks for the long term is a suckers game, or at least has been for the last century. On a 20 year time frame only a few entry months would have made you any money, and those not enough to be worth the effort and borrow cost.

What’s not so obvious from the chart, but must be true if you think about it, is that there must be some sort of irrational herd behavior going on here. It doesn’t make sense for Shiller PEs to fall to 7 or rise to 20. At 7 everyone should be a buyer. At 20, everyone should be a seller. And yet for price to remain at those points (which it has, at times, for years) there must have been both buyers and sellers. Somewhere there was guy happy to sell stocks that would pay his investment back in only 7 years. We call that guy a moron. Similarly, somewhere there was a guy willing to buy stocks that wouldn’t pay him back in 25. That dude’s a moron too.

It’s a good thing these folks exist, because they’re the high level engine that powers profits in the market. Everything else is just the details. It’s the people willing to over or under pay by a factor of two because they’re too uneducated to know otherwise that fuel the whole machine. Without a sucker, there’s no reason to hold a poker game.

In part 3, I’m going to discuss how to go after that dumb money and try to grab a piece for yourself. What I’ve said may sound like fundamentals investing 101 thus far, but I promise we’re heading somewhere more interesting.

Continued in part 3…

Looking forward to your upcoming articles. In the past you have mentioned some very short term trading strategies, but these articles hint at longer term positions. Are you planning on using a combination of the two?

I do both. Since most of my short term trading is futures-based, it requires very little margin/performance bond capital, and that only during regular trading hours. So there’s a lot of room for me to add longer term stuff, and this series in essence documents that.